Katrina 20: The Freeman School’s Story

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, leaving an indelible mark on the region and forever changing Tulane University and the A. B. Freeman School of Business. More than 1,800 people lost their lives in the storm, and damages ultimately topped $200 billion, making it the costliest natural disaster in history in U.S. history.

For the 20th anniversary of Katrina, we asked faculty and staff members who lived through it to share their memories of the storm and their thoughts on its long-term impacts on Tulane and the Freeman School.

The Storm Approaches

On Friday, Aug. 26, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) revised its forecast for Hurricane Katrina, which had formed three days earlier over the Bahamas. For the first time, NHC forecasters predicted that the storm, which had just crossed the Florida peninsula, would turn north and impact the Gulf Coast as a major hurricane.

Venkat Subramanian (professor): We had just moved into our new home the week before Katrina and were at the parish office on Friday doing some homestead exemption paperwork when our babysitter called to tell us about the storm. Upon hearing the news, we shrugged and wondered whether we should just ignore it and ride out the storm at home. But with a 2-year-old and the possibility of no electricity, we figured it wouldn’t be fun, so we started thinking about our evacuation plans.

John Silbernagel (retired assistant dean for graduate programs): On the Friday before Katrina hit, we had a riverboat cruise that evening to close out MBA Orientation Week, and I became increasingly concerned about Katrina’s latest track. I remember standing at the dock as students exited, warning everyone that there was a major hurricane in the Gulf and to take it very seriously. I never saw many of those students again.

Angelo DeNisi (professor and dean, 2005-2011): We came home from a party Friday night and went to bed. My wife woke me up at three in the morning, telling me the hurricane was headed for us. We packed some things in the car, along with our two cats, called to reserve a room at the Four Seasons in Houston, and took off.

On Saturday, Aug. 27, Katrina intensified to a Category 3 storm. As Tulane students and their parents arrived on campus for freshman move-in day, New Orleans officials began urging residents to evacuate.

John Silbernagel: I was on campus to host an open house for the BSM program. I remember talking with many parents from all over the country. They didn’t seem to fully grasp the severity of the situation. Lots of questions about when they should leave for the airport the next day. (My response was leave now.) At some point in the early afternoon, President Cowen moved up the start time of his convocation to announce to students and families to leave New Orleans immediately.

Sharon Moore (assistant dean for academic affairs and chief of staff): [WDSU-TV Meteorologist] Margaret Orr was always a little extra, but I trusted her advice, and she was very clear that we should leave. When we finally got on the road, the traffic was unbelievable. It took us 12-15 hours to get to Houston. My niece was able to get us a hotel as she worked for the Sheraton at the time. Thank goodness, because everything was booked.

On Sunday, Aug. 28, with Katrina intensifying into a massive Category 5 storm, New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin declared a mandatory evacuation.

Harish Sujan (professor): We took till Saturday afternoon to decide to evacuate and then left at two in the morning on Sunday for Baton Rouge. While driving to Baton Rouge (it took about nine hours), Mayor Nagin was on the radio explaining how lethal the storm could be. I wondered if this was just to get people to evacuate to make storm repairs easier.

Venkat Subramaniam: On Sunday at 3 a.m., running purely on adrenaline and toddler snacks, we drove to Opelousas, Louisiana. We were at the hotel by 6 a.m. The problem was, the people staying there decided checking out was optional and chose to stay put, so our reservation was not honored. Just when we were ready to give sleeping in the car a try, a kind policewoman saw us struggling with our two-year-old and took us to a nearby motel, where she helped us find a room.

The Storm and its Aftermath

Early Monday morning, Aug. 29, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in Buras, Louisiana, as a strong Category 3 storm. While initial reports suggested New Orleans was spared the worst of the storm, water began pouring into the city through more than 50 breaches in levees and floodwalls. By Aug. 31, 80% of the city was under water.

Eric Smith (senior professor of practice): I did not evacuate. While the storm was significant, I remember it being more of a windstorm than one having significant rainfall. There were lots of trees down. After the storm, I was out cleaning up the yard when my wife called from California, where she was getting my stepson started in college. (Mobile phones were still working at the time.) When she mentioned the damage to the levees on the 17th Street Canal, I knew it was time to leave.

Angelo DeNisi: We watched the news with other evacuees at the hotel. The storm came and went, and we thought everything was okay, that we had dodged a bullet. And then we started to hear reports of water rising downtown.

Eric Smith: My car was on the top floor of the Tulane parking garage. It had lost a window but was still in operating condition. I was able to get across Willow Street, which was already full of water, and then drive the wrong way up McAlister to Freret and then Calhoun, which were still drivable. I packed the family silver and our bloodhound before driving along River Road, eventually getting to Causeway Boulevard before heading west on I-10.

John Silbernagel: When the storm weakened a bit before landfall and took a slight eastward jog, we thought New Orleans had gotten lucky. Then the levees broke. The 17th Street Canal breach received a lot of coverage, so I knew immediately that my house in Lakeview was inundated. My mother lived fairly close to me, so I knew her house was also inundated. The scope of the tragedy soon became evident, and I just felt numb. There was so much loss on such a widespread scale, it was hard to comprehend.

Sheri Tice (professor): We were in Houston when Katrina hit and actually drove home that same day. There was a lot of wind damage, but there wasn’t yet any flooding. When the levees broke, we left again.

Sharon Moore: Over the next few days, I realized we had a problem. I had to jump into gear as I had my elderly parents with me, my daughter was 4 years old, and I needed to figure out her school situation. My son was in Atlanta. It was a lot! On top of that, our cell phones stopped working, and we all had to learn how to text.

Angelo DeNisi: I had three job offers in three days, but I had always thought about moving to New Orleans and now here I was. I had no intention of leaving.

On Friday, Sept. 2, Tulane President Scott Cowen announced that all classes for the fall semester were canceled. The university’s senior administrative team relocated to Houston to begin planning the university’s recovery and reopening. Tulane ultimately suffered more than $650 million in damage and losses as a result of the storm.

Peter Ricchiuti (senior professor of practice): We had evacuated to my mother-in-law’s house in Opelousas, Louisiana. I was able to make sure that my staff was on direct deposit and that they were getting paid. My wife had gone into town and brought back The Wall Street Journal. She read me an article that said all of Tulane’s essential personnel were in Houston. “Well, this clears that up,” she said. “You may be beloved, but you’re obviously not essential.”

Angelo DeNisi: I met with the other deans and administrators in Houston. President Cowen said we WOULD reopen in January and that our job was to work with that assumption.

Zina Harris Dorsey (director of employee engagement): Tulane was very generous and paid employees through December without our having to report to work.

On Sept. 15, the Freeman School was able to restart its website, and Dean DeNisi began posting updates and answering questions from students and parents. He also began meeting with the Freeman School’s senior administrative staff, which had gathered in Houston to prepare for the upcoming semester.

Angelo DeNisi: The sense of camaraderie among faculty and staff was amazing. All old complaints disappeared, and everyone worked together toward recovery. Someone, and I’m sure it wasn’t me, came up with the idea that the full-time MBA program needed to be revised, and this would be the ideal time to do it. There was this feeling that we had to do something, and a new start for the MBA program seemed like a reasonable idea. That’s when we introduced the Global Leadership Module, which integrated three international trips into the MBA curriculum, and the Applied Management Module, which introduced significant experiential learning opportunities. We accomplished all that sitting around a classroom in Houston.

Venkat Subramaniam: As faculty director I was responsible for helping our MFIN students relocate to other universities during fall. I must have called at least 50 universities, and each and every one was kind, generous and most accommodating. Every one of them agreed to take our students — for free — into their classes, no questions asked. I have never experienced that level of mass kindness from strangers. A Nobel Laureate economics professor even offered his second home in the northeast to any of our faculty needing a temporary home.

Harish Sujan: The morale of the faculty and staff was very high. We were very united, no “I-me-mine.”

Sheri Tice: The faculty pulled together and worked as a team. We are all still very close. It felt like we went through a war together.

Peter Ricchiuti: Camaraderie, gratefulness and warmth were in abundance, but everyone was still asking themselves, “Will I leave Tulane?” I remember going to Mardi Gras six months later and tearing up. The floats were kind of crummy, and the only people watching the parades were our neighbors. I told my wife I had just decided to stay in New Orleans. “I’m going down with the ship.” She told me that quote would probably not be used by the Chamber of Commerce, but I’m glad I stayed.

John Silbernagel: The disaster was something we all went through together, so it brought everyone closer. Personal recovery was more important than work at that time, although work did provide something to keep your mind off everything else. A happy memory was a staff “reunion” at New Orleans Daiquiris on Airline Highway. I don’t recall the date, but it was the first time many of us had seen or talked to one another.

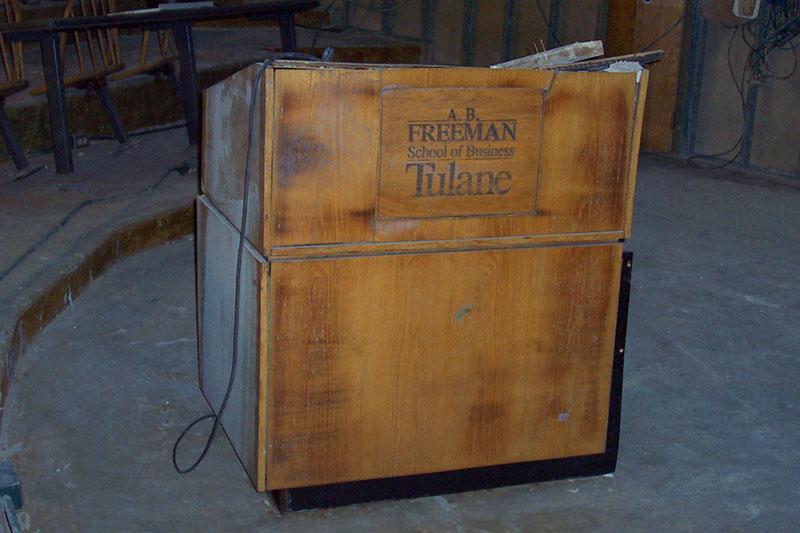

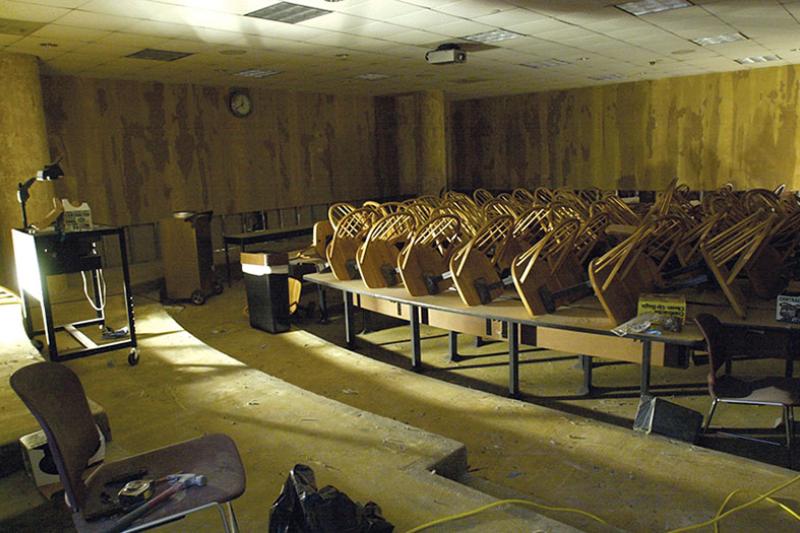

In early October, non-essential personnel were finally allowed to re-enter Orleans Parish, enabling faculty and staff to access Tulane’s campus for the first time since the storm. Goldring/Woldenberg Hall, which housed the Freeman School's undergraduate program and administrative offices, had suffered extensive damage. In addition to broken windows, water infiltration and mold growth, Room 130, a sunken amphitheater-style classroom on the ground floor of the building, was filled with floodwater for weeks.

Michael Hogg (senior professor of practice): I was able to come back into the city before it reopened because I was part of the Tulane administration. The devastation to the city was terrible to see. On the Tulane campus, trash was piled up on the Quad.

Peter Ricchiuti: I had a lot of framed photos and news clippings in my office. They had all yellowed and withered.

Venkat Subramaniam: Thankfully I had lost some weight from all the stress, because there was no way the usual me could have navigated the building, squeezing between dehumidifiers and moisture removing duct work and drain lines. I was shaken by what I saw. If our school was a stock, I am ashamed to say I would have recommended shorting it. I am amazed we came back from that abyss in just a few months. Kudos to the real essential workers!

Zina Harris Dorsey: I was one of the first ones back in the building along with [associate dean] Jerry Hagebusch. I recall throwing all the plants that had died out in the trash.

Sharon Moore: I arrived on campus in October. It was still dealing with downed trees and debris, and the Freeman School was in full swing of remediation. There was equipment everywhere. Our administrators and the IT staff did an amazing job getting everything back in order.

On Dec. 8, President Cowen announced a dramatic restructuring plan to address losses related to Katrina. As part of that plan, the Freeman School was required to reduce its budget by $1.1 million, necessitating the separation of employees, including several tenured faculty members.

Angelo DeNisi: I had to call each one of these people on the phone to tell them that they were going to get a registered letter in the mail and they should look at this carefully because what it was going to tell them is that they had just been fired from Tulane University. This is what we had to do. There was no good solution. My first official act as dean, other than the July commencement, was to fire faculty. A hell of a way to start.

Harish Sujan: We lost half of our marketing colleagues, and I felt terrible for them. I felt that firing tenured faculty was not necessary and that it would have been better to ask everyone to take a pay cut.

Venkat Subramaniam: I didn’t agree with all the elements of the restructuring plan, but the school and the university had to make some tough calls. I wish no one had been laid off, but I too was worried about the long-term prognosis for the school and the university. I am glad we survived. Thank you to the students who returned and their parents who trusted us.

Sheri Tice: I was called to Gibson Hall in September or October 2005. I was told about the Renewal Plan (before it was announced) and appointed to work on a committee writing the rules for the new Newcomb-Tulane College.

John Silbernagel: I think the tough decisions made by President Cowen were instrumental in Tulane’s return.

Peter Ricchiuti: President Cowen went around speaking to parents, students and alums, sharing our plans and optimism. That was comforting when we needed it most.

Sheri Tice: President Cowen gave us hope it would be okay and worked to create good from it. He was the right leader at that time.

An Extraordinary Comeback

Following extensive repairs and remediation efforts, Tulane University reopened as planned on Jan. 17, 2006.

Harish Sujan: Mita [Sujan, professor of marketing] and I did all we could to help the admissions office recruit. We spoke with large numbers of parents and served as ambassadors to the best of our abilities. When Tulane reopened, it was heartwarming to see how close students felt to faculty and faculty felt for one another.

Sharon Moore: I remember the excitement! The faculty, staff and students were extremely excited to get back to what used to be normal.

Michael Hogg: There was a strong sense of community from a student perspective. Despite the devastation that many of my colleagues experienced, everyone came together to ensure the university reopened.

Looking Back: Lessons of Katrina

Today, 20 years after Katrina devastated the city and threatened the survival of Tulane, few vestiges of the storm remain, but its influence on the university and the Freeman School continues to be felt.

John Silbernagel: Freeman is in a much better position to weather (no pun intended) such an event today. More contingencies are in place and communication is better. (Most kids today would not believe that for many of us, Katrina was the first time we sent a text message, because there was no phone service if you had a 504 area code!)

Eric Smith: I think the Freeman School’s focus on both outreach to the community and our energy-agnostic approach to teaching about energy has become a big plus for us when dealing with economic policy issues in the city as well as the state. We have heard from students who are not from Louisiana that this emphasis was a primary differentiator when they were deciding on where to attend school.

Zina Harris Dorsey: Resilience, dedication, hard work and perseverance have become part of the spirit of Tulane and the Freeman School.

Sheri Tice: I think going through Katrina helped us get through COVID. We approached COVID with a similar ferocity and determination to open.

Michael Hogg: The Freeman School is much more focused on experiential learning today, and, from an undergraduate perspective, students can major across schools much more easily.

Angelo DeNisi: Before Katrina, I think Tulane saw itself as being in New Orleans but not part of New Orleans. After Katrina, that all changed. New Orleans and Tulane were one and they were always going to be tied together. That became clear. To me, that’s the biggest change — the attitude that the university has about its relationship with the city.

Interested in advancing your education and/or career? Learn more about Freeman’s wide range of graduate and undergraduate programs. Find the right program for you.

Other Related Articles

- AI-powered fund takes top prize in Aaron Selber Jr. Hedge Fund Course

- Alum brings rugby mindset to new consulting program

- Keeping it cool: MBAs help Convention Center find its temperature sweet spot

- Investopedia: Rising Inflation and Slowing Growth Are Investors' Worst Nightmare

- Forbes: AI Eating Tech And Other Jobs? It’s A Matter Of Perspective

- Alum shares playbook on forensic accounting

- Research Notes: Paulo Goes

- Freeman students make Madrid their classroom