A Recipe for Remembrance

Dining on a meal of roast turkey, potato circles, semolina sticks and walnut cream cake, Steven Fenves marveled at the spread before him.

“What I tasted was really terrific,” said the 93-year-old Auschwitz survivor, musing over the redolent flavors. “The semolina sticks were all very authentic.”

Fenves had stepped back in time, savoring the taste of his mother’s recipes for the first time in 80 years. The experience reconnected him to his childhood in Yugoslavia and awakened memories of a happy life before it was torn apart by World War II.

“Before this tragedy, they were regular people living a nice life. The project captures the life of this family before the Holocaust in a way that’s really humanizing.”

Alon Shaya, Chef-Partner, Pomegranate Hospitality

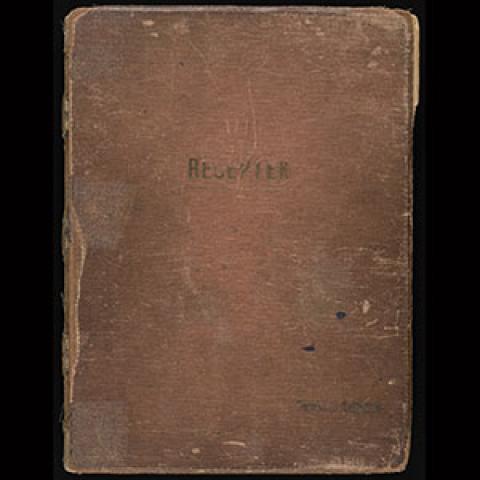

Collected in a tattered, cloth-bound ledger book, the recipes were almost lost forever. Rescued by the family’s cook in May 1944 as Steven, his sister and their parents were deported to concentration camps, the recipe book likely would have remained a dusty artifact in the collection of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum if not for the work of Emily Shaya (BSM ’06, MBA ’13), her husband, chef Alon Shaya, and their friend Mara Baumgarten Force, professor of practice at the Freeman School.

Their discovery of the book set in motion an inspirational journey that has reenergized Fenves and put his family’s long-lost recipes back on dinner tables. They dubbed their effort Rescued Recipes.

To date, nearly 1,000 people have attended Rescued Recipes dinners across the country to learn Steven’s story while tens of thousands more have seen coverage in The Washington Post, NBC Today, the Hollywood Reporter, Fox News, CBS Sunday Morning and other outlets.

“We know that people, especially young people, learn from and are deeply impacted by individual stories,” says Jed Silberg, associate chief development officer for national philanthropy at the Holocaust Memorial Museum. “We owe Emily, Alon and Mara a debt of gratitude for telling this story and connecting the power of food and memory.”

“Generations of family histories and family traditions were obliterated during the Holocaust,” says Force, whose grandparents were Holocaust survivors. “This project reanimates and gives life to that past.”

As director of new projects at Pomegranate Hospitality, the restaurant group she owns with Alon, Emily Shaya sits at the helm of a restaurant group that has garnered local and national accolades. Their restaurants regularly appear on “Best Of” lists in publications like Esquire, Bon Appétit, The New York Times and Conde Nast Traveler, and Alon has earned a host of prestigious awards. In 2015, he won the James Beard Award for Best Chef in the South, and in 2016, he won the James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant in America.

Beyond their culinary success, the Shayas are also involved in a host of public service activities, including partnering with local non-profits to educate young culinary workers and donating thousands of dollars to local charities.

“We can’t just be off by ourselves,” Emily says of their service activities. “It’s really important for us to have a relationship with the New Orleans community.”

Emily’s relationship with New Orleans began in 2002 when she arrived from Calhoun, Georgia, as a first-year student at Tulane University. As a business major, she wasn’t initially drawn to hospitality and instead pursued opportunities in real estate and finance. After graduating in 2006 with a Bachelor of Science in Management, she landed a job with Woodward Interests, a New Orleans-based development company. “While I was there, I learned about project management and how to put projects together,” she says.

Overseeing real estate projects may seem a far cry from managing restaurants, but Emily drew on that experience when she entered the hospitality industry. In 2017, she and Alon, whom she married in 2012, founded Pomegranate Hospitality to create, according to its mission statement, a space for meaningful, lasting relationships, community engagement, cultural diversity, and personal and professional growth. A year later they opened two modern Israeli restaurants under the Pomegranate banner: Saba in uptown New Orleans and Safta in Denver. Looking back, Emily sees the connection between her education at the Freeman School and her work in hospitality. “Really, those restaurants were real estate development projects,” she says. “I took that real estate expertise and applied it to the first two restaurants we opened.”

Following the success of Saba and Safta, the Shayas partnered with the Four Seasons Hotel in New Orleans to open Miss River and the Chandelier Bar. In 2023, they introduced another restaurant, Silan, at the Atlantis Paradise Island Resort in the Bahamas, and in 2024 they launched Safta 1964, a limited-run celebrity-chef residency at The Wynn Las Vegas.

When it comes to running Pomegranate Hospitality, Emily says her business mindset complements Alon’s culinary focus. “We both have our different strengths,” she says. “And we collaborate on the vision.” While Alon oversees menus and food production, Emily makes hiring decisions, supports staff and develops partnerships to advance the company’s philanthropic goals.

Not only have her business skills helped Pomegranate Hospitality grow, but they’ve also allowed the company to pursue charitable causes. Force says that Emily plays an important role in that. “Alon and Emily are both incredibly generous, but to be able to sustain that, you need to run a tight ship,” she says. “And Emily is a magnificent businesswoman.”

In addition to strong philanthropic values, Emily is also committed to bringing jobs to New Orleans.

“We started this company in New Orleans with just a few people around our dining room table at our house, and now we have an office just down the road from Tulane with nine people just in our executive office,” she says. “I’m proud to have brought this new type of job to New Orleans.”

Beyond their restaurants, Emily and Alon are also creating a pipeline for the next generation of restaurant workers. “We think it’s super important to support training infrastructure,” she says. “And give people opportunities in the culinary arts.”

Each year, the Shayas host a fundraiser to benefit the New Orleans Career Center (NOCC), whose culinary program provides career training for students entering the hospitality sector. Emily and Alon also support up-and-coming restaurateurs through the Shaya Barnett Foundation. Conceived with the help of Alon’s high school home economics teacher, the foundation offers educational opportunities for students looking to work in the food and beverage industry. The foundation provides kitchen equipment and lesson plans for teachers and liaises with local chefs to bring hands-on cooking demonstrations to students.

“What Emily is doing in her businesses is an extension of the service-learning we teach here at Tulane,” says Force, “and it’s fantastic to see.”

Managing a restaurant means balancing the strategic vision with an acute attention to detail. When she’s not laying the groundwork for future Pomegranate Hospitality ventures, Emily oversees the minutiae that make for a memorable dining experience. “The way people feel when they’re in the restaurants is really important to us,” she explains. “And it all boils down to the finishing touches. What are the finishes on the walls? What kind of seats are you sitting on? What are you touching while you’re eating the food?”

“With everything we do,” adds Alon, “there’s meaning and a story behind it.”

Stories are served in abundance at their restaurants. At Saba, they reveal themselves in the restaurant’s name. Hebrew for grandfather, it evokes paternal stories passed down from generation to generation and hints at the cultural traditions of the restaurant’s Israeli and Mediterranean cuisine. Dishes like matzoh ball soup, lamb kofta and classic tahini hummus evoke Alon’s youth in Israel, where he lived until he was 4 years old. Miss River, the Shayas’ restaurant in the Four Seasons Hotel, tells a different story, one that begins much closer to home. A “love letter to Louisiana,” the restaurant draws inspiration from the culinary traditions of the South and Emily’s upbringing in Georgia. With a menu boasting duck and andouille gumbo, Emily’s red beans and rice with buttermilk fried chicken, and butter-fried beignets, Miss River chronicles the food culture of the South.

Perhaps the most important story the Shayas have helped to tell is that of Steven Fenves.

Born into a wealthy family in Subotica, Yugoslavia, in 1931, Fenves enjoyed a happy childhood filled with parties, travel and meals prepared by the family’s cook, Maris. Fenves never knew her last name.

When he was 10 years old, however, his life changed forever. Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia, and Subotica was annexed by Hungary. His father’s publishing business was seized, and the family was forced to live in a corner of their apartment with Hungarian officers occupying the rest. Three years later, in March 1944, German troops occupied Subotica, and the Fenves family were pulled from their home and sent to concentration camps. As neighbors looted their home, Maris sneaked in and rescued a few of their personal possessions.

“She was a hero,” Alon says. “She went into the Fenves family apartment when they were being taken out and sent to Auschwitz. She went in and saved the family cookbook.”

At Auschwitz, Fenves worked as an interpreter for the German Kapo. While his language skills provided him with some degree of protection, he was forced into slave labor at a German aircraft factory. Later, as it became clear that Germany would lose the war, the Nazis sought to erase all evidence of extermination camps. Fenves and his fellow inmates were sent on a death march to Buchenwald. The morning after his arrival — April 11, 1945 — American troops liberated the camp.

Fenves and his sister, Estera, survived the war, but they later learned that their mother and grandmother had died in captivity. Their father died a few months later.

Years later, after Fenves immigrated to the United States and became a pioneering professor of structural engineering, Maris found him and returned the cookbook. Instead of keeping it, Fenves donated it to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in the hope that it would help educate the public about the horrors of the Holocaust.

In fall 2019, Mara Force was speaking at a Jewish Federation of Greater New Orleans event when she shared the story of her grandfather, Misha Meilup, a Lithuanian Holocaust survivor. One of the few possessions he brought with him to America after the war, she said, was the spoon he had used to eat with while imprisoned at Dachau. Embossed with a Nazi eagle, the spoon was worn on its side from being scraped against the bottom of his bowl during his imprisonment. On Jewish holidays, Force said, her family uses it as a serving spoon to remember their shared history and celebrate the life they now enjoy thanks to their grandfather’s resilience and the generosity of the American Jewish community that took him in.

Alon Shaya was in attendance at that event, and he immediately approached Force to tell her a story of his own. He had recently visited Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust museum, where he’d viewed one of its best-known artifacts, a flag from a concentration camp bearing the hand-written recipes of inmates. The women of the camp had added their favorite recipes to the flag to sustain themselves in a time of hunger and deprivation. Deeply moved, Alon was struck with an inspiration: What if he were to cook those long-lost recipes to celebrate the life and spirit of those brave prisoners?

He reached out to Yad Vashem, he told Force, but the museum said it wouldn’t be possible.

“I told him it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever heard,” Force recalls. “I told him I have a relationship with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., and I’m sure they won’t shoot you down.”

Force reached out to the museum’s Jed Silberg, and he arranged for archivists to pull everything they could find related to cooking and recipes. A few months later, the four of them — Force, Silberg, Emily and Alon — were at the museum sifting through artifacts when a tattered book caught Alon’s attention.

“We came across this cookbook called ‘The Fenves Family Cookbook,’” Alon recalls. “The staff at the museum told us Steven was still alive, so we reached out.”

Charmed by the chef’s sincerity and enthusiasm, Fenves quickly became friends with the Shayas and agreed to translate the recipes from their original Hungarian. Communicating via Zoom and Facebook, Alon and Steven explored the recipes in the book, discussing their flavors, textures and appearances. One by one, Alon prepared the dishes, adjusting ingredients and adapting methods according to Fenves’ recollections, until finally he was ready to put his work to the test.

“We wanted him taste his mother’s cooking,” Alon says. “So we began sending dishes to him packed in dry ice.”

Almost immediately, Emily noticed a change in Fenves’ demeanor, as if the flavors had unlocked something deep in his brain. He started to regale them with stories of his childhood in Subotica. He described going to the market with his mother, pickling vegetables and watching Maris prepare family meals in their kitchen.

“He lit up,” she recalls. “He started telling us his childhood memories.”

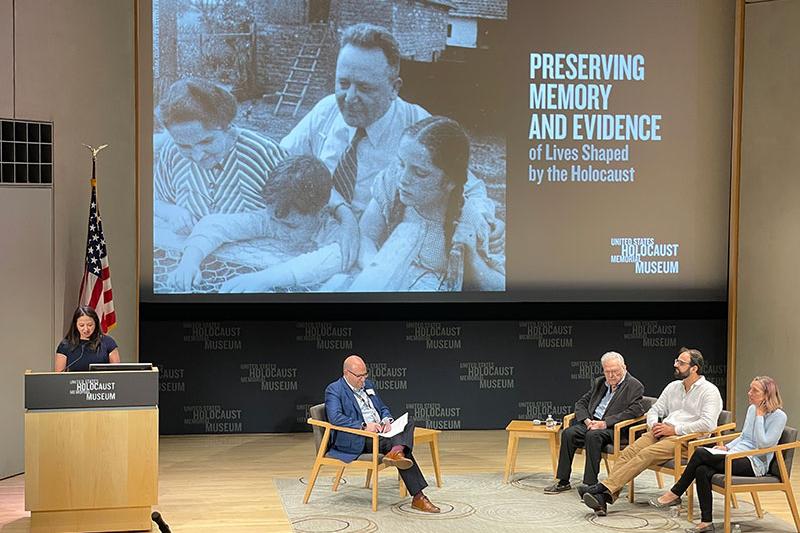

In the fall of 2020, during the height of the pandemic, the Shayas partnered with the Holocaust Memorial Museum to host a fundraiser on Zoom highlighting their effort to preserve the Fenves family’s recipes. Force spoke briefly about the project, and then, from his home kitchen, Alon prepared the Fenves family’s recipe for semolina sticks; Emily operated the camera. At the conclusion of the livestream, viewers were invited to make a donation.

The event ended up raising $50,000 for the museum.

When pandemic restrictions finally eased, the Shayas and Force decided to take Rescued Recipes on the road. In June 2022, they hosted a dinner at the Washington D.C. home of cookbook author Joan Nathan. During an evening of remembrance, 100 guests came together to hear Fenves’ story and share a meal inspired by his family’s recipe book. The event raised $180,000 for the museum.

From that first meal, Rescued Recipes grew into a series of fundraiser dinners across the country. With Force helping with locations and guest lists, the Sazerac Co. donating liquor, and Emily and Alon overseeing the menus, Rescued Recipes has to date hosted events in Atlanta, Chicago, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, New Orleans, New York and Philadelphia. TV personality Phil Rosenthal, star of Netflix’s “Somebody Feed Phil,” hosted the dinner in Los Angeles, and Falcons owner Arthur Blank hosted in Atlanta. Proceeds from the events go directly to the museum’s preservation efforts, helping to digitize archival materials – like the Fenves family recipe book — and make them accessible to the public.

“Rescued Recipes has helped the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum raise over $800,000 in the past three years to support the collection and conservation work that we do,” says Silberg. “That impact is a direct result of the vision and dedication of Emily, Alon and Mara.”

While Rescued Recipes has touched countless lives, the person most affected by it is undoubtedly Steven Fenves.

Prior to meeting the Shayas, Fenves served as a docent at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, helping to educate visitors about the atrocity and offer his testimony, but after a few years of volunteering, he’d grown tired of recounting his trauma.

“He had gotten kind of weary of being a docent and talking about his experience,” Emily says.

“How do you talk to a 15-year-old about Hitler?” Alon adds. “It’s not an easy conversation.”

Fenves was considering stepping away from his duties at the museum but meeting the Shayas changed his outlook. “When we discovered his story and started talking to him about it, it gave him a renewed passion for sharing his experience,” Emily says. “It was an opportunity to tell his story from a more positive angle.”

Unlike other survivor accounts, the Rescued Recipes project presents a more complete version of the family’s story, so his life — and the lives of other survivors — isn’t defined solely by sorrow.

“Before this tragedy, they were regular people living a nice life,” says Alon. “The project captures the life of this family before the Holocaust in a way that’s really humanizing.”

“The Holocaust looms so large,” says Force. “It’s so nice to be able to think about the joy of the before-times. Ultimately, it’s a celebration of life.

“Food can nourish not just your body but also your soul,” she adds. “How can you not have empathy for somebody whose food you’ve tasted?”

And for the Shayas, food is a common language that people of all backgrounds can understand.

“Food spans generations and demographics,” Alon says. “It connects people. Rich or poor, white or black, Jewish or non-Jewish, and everything in between.”

The next Rescued Recipes dinner will take place in Denver in June 2025. For more information and to register, visit the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website.

Interested in advancing your education and/or career? Learn more about Freeman’s MBA programs. Find the right program for you.

Recommended Reading

- How to Choose an MBA Concentration

- Finance Curriculum vs. Accounting Curriculum: How Are They Different?

- What Will You Learn in an MBA Curriculum?

- Business Analytics vs. Finance: Which Master’s Degree Is Right for You?

- Part-Time vs. Full-Time MBA

- What Is a STEM-Designated Degree Program?

- Types of MBA Degrees

Other Related Articles

- Undergrads help high schoolers build investment portfolios

- Goes highlights growth, AI initiatives in ‘State of the School’ address

- Fast Company: Are we in a K-shaped economy? Delayed employment numbers could reveal recession odds

- Newsweek: The Real Cost of Layoffs Isn’t In the Financials

- Conference explores opportunities in alternative investments

- Keeping it cool: MBAs help Convention Center find its temperature sweet spot

- CNN: Stocks rise ahead of tech earnings as Nvidia hits $5 trillion valuation

- Freeman Futurist Series looks at AI, Robotics and Quantum